What do we do with biblical passages the forecast something that we know isn't true? In Chapter 7 of Second Samuel, God says that the throne of David will last forever, a statement that ceased to be true thousands of years ago. This passage has been co-opted into other faiths beyond Judaism in an attempt to make it seem true. For example, in Christian theology the matrilineal line of Jesus is traced all the way back to David, establishing the central figure of that religion as a rightful heir to monotheistic leadership and, by merit of his rule in heaven, maintaining the veracity of God's message to David through the prophet Nathan. For those who don't ascribe to tenets of Christianity but still value Bible study, this particular passage can be a real sticking point.

For Jews, we read a scriptural text that says one thing yet we see the real world fail to reflect it. Does this negate the value of the book? As with most religious contemplation, the only real problem comes with direct, literal interpretation. If we need the Torah to be the unfiltered word of God, then contradictions like Second Samuel, Chapter 7 call the entire book, even the entire faith into question. Taken as a human text, biblical contradictions aren't nearly as problematic.

Given the period in which it was written and the way the narrative is arranged, the two Books of Samuel can be seen as a partial history and partial commentary on Israel's experiment with monarchy. It is a text that seeks to establish a positive public image for its protagonist, David, while defaming his contentious predecessor, Saul. If this story is a pro-House-of-David public relations campaign, it only makes sense that it would claim the perpetual supremacy of David and his throne.

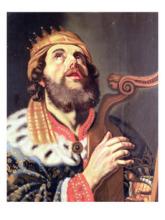

But the Books of Samuel don't paint David as a perfect ruler. This is the true value of the text. David is indeed chosen and more frequently righteous than sinful. He's a great leader and an easily likable guy, but he's still as fragile and weak as any other flesh-and-blood person.

This has a two-fold lesson, one that is repeated throughout the Torah and one that is unique to David's story. First is the idea that even the best among us are flawed. In this sense, David reflects Moses, another great but troubled political leader in scripture. At the end of his life, Moses was called the best man among his people, a people chosen by God above all others. Yet Moses was far from perfect. He was hot-headed, short-tempered and more often reluctant than devout. So David, for all his piety and propriety, is likewise a great but flawed leader. He is occasionally arrogant, lustful and emotionally frail. He has a pattern of pursuing his own personal engagements, however good his intentions, even if doing so puts those he loves in danger. David is the best leader God could make of a man, which turns out to be insufficient for the needs of the people.

The Books of Samuel are a people's document of monarchy. They tell the story of great, capable men who can't even do what's necessary for a nation with all the resources of royalty and the blessings of God. In this somewhat jaded commentary on the nature of kingship is the second lesson of the story. If even the most generous text in support of a political faction won't ignore that faction's faults, perhaps the conclusion to which the ancient Israelites came concerning monarchy is that it is unsuitable for a people of law. If David's throne is not eternal as the text says it will be, then maybe the lesson of this bit of scripture is that there is no such thing as a divinely anointed king, that society can't rely on individuals to assure its continued existence.