The book of First Samuel has a lot of very interesting ideas. Perhaps the most interesting is its clear assertion that it's wrong, possibly even a sin, to ask for a king. It's important to remember that, according to this story, Israel didn't have a king prior to Saul. It was only in a moment of desperation as the nation was on the brink of being conquered by the Philistines that the people begged for an absolute ruler. The book spends the duration of its length describing just why asking for a king is the worst thing a nation can do for itself.

As the prophet Samuel often explains, the enemies of Israel only gained so much ground in the first place because Israel had largely breached its contract with God, thus nullifying any protection God had promised in return. The people were neglectful of their spiritual duties, which in Judaism mostly involves day-to-day responsibilities toward other people, so their personal failings resulted in a weak nation. By not holding themselves accountable under the law, the Israelites put themselves in a position to be conquered from without. In essence, the people asked for a king because they no longer wanted to be responsible for their own nation.

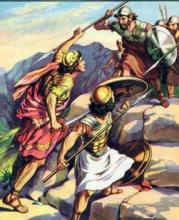

The story of Saul addresses the inherent flaw of absolute monarchy, namely that under it a nation is only as good as its king. Saul has a strong start but it doesn't take him long to stumble. Just two years into his hard-won reign he lets his proclivity for overly flexible interpretation of laws get the best of him. Saul makes ill-advised decrees, like imposed fasting and the keeping of political prisoners, while simultaneously bending to the capricious will of his people regardless of whether or not they want what's right. In short, Saul conducts his office like a self-styled priest with no real moral compass. This results in an atmosphere of chaos, with people on both sides of his constant war following whatever urge comes upon them without ever considering the consequences of their actions. For this lawlessness, Samuel informs Saul that he's fallen out of God's favor and will soon be replaced. That replacement, of course, will be David.

What's most interesting about the wild days of Saul's rule is that the king still pays lip service to God in the form of sacrifice, but he goes about it in such a way that it actually defies God's explicit instructions. When Samuel confronts Saul, he explains that ritual is empty if it contradicts actual righteousness. This is a very important lesson, one of the most important in Jewish philosophy. Holiness is not in the somatic, the sensual or the scripture, it's in the mindfulness of an action.

The lessons in First Samuel chapters 12-15 can be easily applied to our lives today. As so many nations in the 21st century struggle, it's wrong for us to ask for leaders to fix every problem we have, not just because we have responsibilities unto our own nations but because no leader is even capable of such broad reform. Righteousness and law are now and have always been the responsibilities of the governed, not just those who govern them.