Shabbat Shalom and welcome to Judeo Talk. In this week's Torah portion, Vayeitzei, there is a very interesting use of a particular motif. The parsha begins and ends with the laying of a pillar, but what those two pillars symbolize could not be more different.

The parsha opens with Jacob's journey from home. He travels alone from Be'ersheva toward the land of his cousin Laban. While he is on the road, Jacob settles down to sleep on a rock. It's there that he has his famous dream depicting a ladder to heaven where he speaks with God and the family covenant is reiterated. As a side note, it should be apparent by now that each generation after Abraham has had to accept the covenant individually. Just like sins aren't passed down to the next generation, blessings and agreements require renewed commitment as well. This is going to be especially important in the later books of the Tanakh when the Israelites wander in the wilderness struggling with righteousness and law. They are obviously not entitled to the Promised Land just by merit of being in Abraham's line. They have to accept the covenant and hold up their end of the bargain.

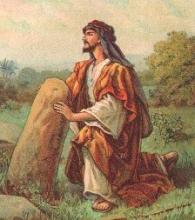

When Jacob awakes from his dream, he recognizes that he just had a holy experience so he sanctifies the rock on which he slept and he lays a pillar to mark the spot. He names the place Beth-El (House of God) and then continues his journey. In this instance, the pillar represents the extent of holy places, that a person can have powerful spiritual experiences anywhere in the world. Even unremarkable places as plain as a rock on a blank path can be the scenes of important moments in life. Jacob's pillar is the sign of just how open life can be.

When Jacob arrives in Laban's land he falls in love with Laban's daughter Rachel, eventually marrying both Rachel and her sister Leah. From there Jacob has many children, the ones that will eventually come to establish the twelve tribes in Exodus. He stays in the land, working for Laban as a herder and mostly being at peace. At some point, relations between Jacob and Laban sour and they come very close to open combat. When all is said and done, the best solution they can muster is to set a pillar marking where one's land ends and the other's begins. In modern terms, Jacob and Laban are setting borders, fences, even walls just like the Berlin Wall, the proposed wall at the border of the United States and Mexico or the wall between Israel and Palestine.

This second pillar is the opposite of the first. Instead of symbolizing the openness and possibilities of the world, it represents the way we put things between ourselves and our neighbors out of an inability to forge peace. When we look at the structures we build in our lives, whether literal or figurative, we should ask ourselves whether we build them to recognize something good or to separate ourselves from others. Are our synagogue or church walls there to mark a place where people can gather, or do they primarily exist to keep disagreeing neighbors on different sides?