Shabbat: Parsha Emor

Shabbat Shalom and welcome to Judeo Talk. The Torah Portion for this week is Parsha Emor, Leviticus 21:1-24:23.

This parsha is what I like to refer to as a "little things" parsha. Instead of having one major theme throughout, it issues several smaller, mostly unrelated items. Emor reiterates some old laws, reminds the people to observe certain holidays and it even has a fun linguistic lesson in the middle.

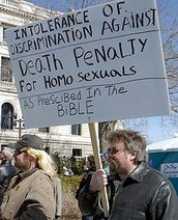

The first thing that springs to mind when reading Emor is the focus early in the parsha on unblemished things. God forbids priests who have some blemish or deformity from performing public rituals, though they are still permitted to carry out the private rites of the priesthood. Similarly, God emphasizes the importance of using only unblemished animals for sacrifice. Though these two laws are on a similar topic, it's not likely that they stem from the same line of reasoning.

The easier of the two to parse is the use of unblemished sacrificial animals. In addition to forbidding the use of blemished animals, God also makes note of sick or injured creatures. The implication here is simple. Sacrificial animals came from one's personal livestock or by purchase from someone else. The point of sacrifice is to feel a loss, to give up something of value. Sick, injured and blemished animals are worth significantly less than strong, healthy, unblemished animals. This law is meant to require people to take their religion seriously. Sacrificing a cheap creature is hardly a sacrifice at all.

As for the limits placed on blemished priests, this is not meant to put an inherent value on a human life, but more as a means to maintain a public image. The priests were revered leaders in their communities. Just like President Franklin D. Roosevelt was forced to stand through the pain of his polio-effected legs so that he might project an image of strength and dignity, the priests of Israel had to project an image of purity and health to the people they served. Our clergy today certainly deal with similar circumstances. There are many behaviors that are simply unacceptable for our rabbis because of their responsibilities to the communities they serve.

After all the blemish-related laws, God reiterates the importance of properly observing two specific holidays. First is Passover, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, and the second we would recognize as Sukkot, the harvest festival during which it is a mitzvah to sleep in the Sukah, or booth. The concept on which God focuses this time around is the prohibition of working during these observances. Just like we are not supposed to work on Shabbat, neither are we supposed to work during other holy days. The interesting linguistic tidbit here is that the Torah has to add a modifier to the word for "work" in order to distinguish it from prayer. The Hebrew word Avodah on its own is used to mean both "work" in the traditional sense but also "worship". To indicate the former, the Torah adds a term that basically means "servile" or "daily, mundane, non-holy" work.

We are approaching the final parshiot for Leviticus and soon we will be moving into some of the more obscure laws of the Torah. The focus shifts away from sacrifice for the most part, so we can say that sacrifice is the general theme of Leviticus. With major rituals out of the way, the Torah turns its attention to daily life. Before that, we still have a few lessons left. I hope you'll join us for further study each week. Shabbat Shalom.