When the people of Judah first demanded a king, it was out of desperation. There was a sense that everything was chaotic and that the entire civilization was on the brink of extinction. Foreign powers constantly assaulted the country with impunity, the fundamental laws of the society were being ignored or circumvented by the privileged and it seemed that even God had abandoned those who considered themselves chosen. Even for us readers, the disorder of this period becomes so commonplace that we forget just how savage everything was. Saul's reign did little to fix this state of perpetual decline. In chapters eight and nine of Second Samuel, it becomes increasingly clear that David's time on the throne isn't about improvement so much as it's about returning his nation to a livable condition.

Chapter eight of the book is dedicated to David's many conquests after the establishment of his kingship. In addition to routing the Philistines, he also takes on a number of other nearby enemies, going as far as Damascus. As with just about any ancient text, the extent of David's military prowess and the numbers involved with the individual wars are quite inflated. At one point the chapter claims some 22,000 infantry soldiers in David's army, which was something of a physical impossibility during that period and in that location. Ancient Israel simply didn't have the population or raw resources to create, outfit and feed such a massive army.

Once again, we have a biblical passage that diverges from reality, so we have to ask why. The clearest motivation for this hyperbole of martial might is simply an attempt to instill pride in the people who read the book. It's a moment in which exiled Jews can say, "We weren't always a meek minority". Taking this from a different angle, there's another lesson about the nature of nationhood and civilization in general. Just like last week's passages and their ironic claim of the perpetuity of David's throne, there's a warning implicit in David's supposedly massive army. If one kingdom's military was once an unstoppable juggernaut and now no longer exists, does that not imply that there is no such thing as an army that cannot be defeated? For Jews in exile, there's a kind of comfort in this sentiment. Whether it's David's 22,000-deep infantry, the Third Reich's 18.1 million total servicemen during its decade-long existence, or even the United States' current 2 million individuals in active and reserve duty, no military is so large or elite that it will exist forever. For the small cultures of the world, this is reassuring. For the large, it's humbling.

Though David's conquests in chapter eight are meant to paint him as a strong, proficient ruler, there's yet another element to his military campaign. David isn't assaulting other nations for glory, profit or malice, he's simply setting his house in order. At least according to the book, David dedicates the spoils to religious ends and not to his own treasury, and the enemies he fights are those who attacked Israel and Judah many times in the past. However grand and violent this period is, its purpose is the re-establishment of stability and law. David is mostly cleaning up bands of raiders, not toppling sovereign nations for the sake of empire.

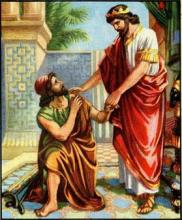

As depicted in chapter nine, David isn't exactly wrathful. When the time comes to face the many internal problems of his country, David inquires after the remaining members of Saul's fallen house. The only living heir to Saul's line is the crippled son of Jonathan, Mephiboshet. He has been living in the country with someone named Machir, unable to have much of a life because of his physical disability. David calls Mephiboshet to his court and grants him the remainder of Saul's familial land, also inviting him to live among the nobility under David's own patronage. This isn't so much an act of extraordinary kindness as it is a recognition of established law. According to the Torah, one generation is not automatically supposed to bear the guilt of their parents' sins. Mephiboshet is two whole generations removed from any wrongdoing and he never challenged David's rule. He is considered therefore without sin and is entitled to the inheritance that should have been passed down to him after the death of his father and grandfather. This is David's way, at least for most of his rule. He attempts to create order through a combination of national security and unwavering interpretation of the law. This is why he is considered a great king.