David the King: The Sons of Goliath

In the final chapters of Second Samuel a lot of energy is spent simply putting David's house in order, both to sweep up after the decades of civil discord and to prepare for David's fast approaching exit. It becomes especially clear in Chapter 21 that, despite David's successes, his country is still a mess. There are so many problems, so many improprieties accrued over the years that David and his ever-shifting cadre of advisors seem to just lose track. The fatigue in David that begins around the time of his scandalous relationship with Bath-Sheba comes to full fruition in the last few chapters of his story.

Chapter 21 opens with a three-year famine that strikes Israel in the winter of David's life. When David finally consults God, he learns that it is the delayed retribution for one of Saul's own crimes. During his last wrathful years on the throne, Saul ordered the extermination of a group of people called the Gibeonites, a fairly harmless faction of the formerly glorious Amorites. The long relationship between Hebrews and Amorites is important to remember and it is no mistake that they come up in this story. Back when the Israelites were first coming into the Promised Land after wandering the desert with Moses, the Amorites were considered their most formidable foe. They were described as being unusually tall and especially adept in battle. Though the Israelites swept across the lands leading into Canaan with relative ease, they were advised to avoid the Amorites until the very last battle before establishing their nation. In the time of David, the last Amoritic people, the Gibeonites, have a holy peace treaty with Israel that is broken by Saul out of sheer paranoia.

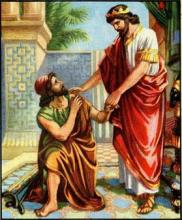

The fall of giants is the central theme of Chapter 21. Some are giants who fell for their needless assaults on the peaceful, others who fell out of hubris or simply as a matter of course. At the end of the chapter the physical giants descended from Goliath all die one by one in battle against Israel when the Philistines resume their war, though the entire chapter is dotted with the fall of figurative giants in royalty as well. The descendants of Saul, excepting Mephibosheth who is protected by covenant, hang for Saul's crime against the Gibeonites while we are reminded of Saul's own defeat when his and Jonathan's bones are finally rescued from their tomb in the foreign land of Jabesh-gilead.

Chapter 21 even has the beginning of the fall of David himself. As the wars with the Philistines drag on, the aged David can no longer perform in battle. He nearly dies in a fight against the first of Goliath's sons, at which point his captains refuse to let David return to war. This one thing that was always David's strong suit, war, leaves him and he almost falls to a considerably less threatening version of the enemy whose defeat made him famous in the first place.

The lesson here is that no individual is immune to time. Israel is so dependent on David's leadership, yet it is obvious at this point in the story that he no longer possesses the full faculties to lead. As always, the tasks of defense and law fall to the next generation, though that generation lacks any one individual who can do as David did in his youth. There is a warrior strong enough to kill a giant, but not all the giants who threaten the land. Even then, those warriors are not posited as great leaders or arbiters of law. The society, in a sense, returns to delegating special tasks because the truly great, the Davids of the world, are few, far between and not even all that consistent.