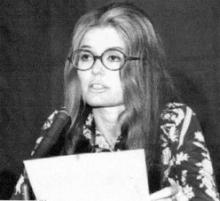

Person of the Week: Gloria Steinem

Judaism, among all Abrahamic faiths, pays particular attention to the iconic women in its scriptures and history. While biblical texts can hardly be called non-sexist in even the loosest modern context, the stories of the Torah are downright radical for their time concerning social issues. It should come as no surprise, then, that Jewish women have stood at the forefront of political progress throughout history. Many of the most important individuals in thought and in action during the major strides in civil rights in the 20th century were Jewish women. Of them all, none are as famous or as overtly influential as Gloria Steinem.

Gloria was born to Leo and Ruth Steinem in Toledo, Ohio in 1934. At the age of 10, Gloria saw her parents part ways. Her father spent much of his time in California where he searched for steady work and her mother eventually experienced a nervous breakdown and subsequent mental instability with which she struggled for the rest of her life. Despite these problems at home, Gloria was a driven student, attending Smith College and making some coin teaching college calculus until she found her first journalism job with Help! magazine in 1960.

Help! was a light, humorous culture periodical. It wasn't until 1962 that Steinem wrote her first serious political piece as a freelancer for Esquire magazine, a powerful article on the concept of contraception and the social struggles of women in the workplace. This began a trend in Steinem's career of writing important but controversial pieces. Her talent and forward-thinking philosophy led to a job as one of the founding members of New York magazine. While there, Steinem founded Ms. magazine, the most popular feminist publication in America to date.

Through her famous writings, Gloria Steinem became one of the most well-known figures in the feminist movement of the 1960's. Just as important as her writings, she helped introduce the world to some other very influential feminist leaders. Steinem served as a co-founder of several major mainstream feminist organizations, such as the National Women's Political Caucus, the Women's Action Alliance and the Coalition of Labor Union Women.

Gloria Steinem's most famous work is the Address to the Women of America. This speech called for no less than the entirely equal treatment of all people in the United States regardless of sex or race. The key statement of the Address is the line, "We are talking about a society in which there will be no roles other than those chosen or those earned." This is the core of so-called Second Wave Feminism and Gloria Steinem is a living example of its sentiment.

Though her name is synonymous with feminism, Gloria Steinem should rightly be called an active political philosopher. To this day she maintains a hands-on approach to the betterment of society as a whole through whatever channels fit best. She has been a vocal supporter of reproductive rights, equality under the law for LGBT Americans and improved prevention of domestic violence.

At the age of 75, Gloria Steinem remains an integral part of social progress in America and around the world. She has battled illness, including a 1986 breast cancer diagnosis, and political opposition to promote the continued creation of a better, more peaceful society.