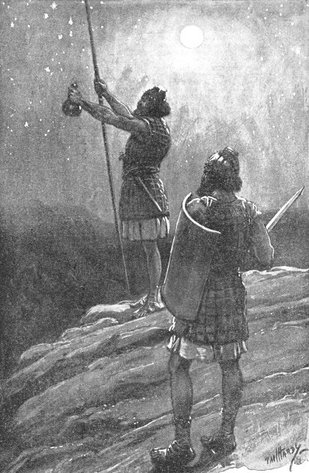

David the King: David in Gath and the Ghost of Samuel

Jewish culture has a complicated history with its sense of nationhood. Like any people, we strive to have a sovereign country of our own, yet so much of Jewish identity comes from the experience of being the outsider. All but one of our biblical founders, Isaac, spent a great deal of time as guests in a foreign nation and the epic story of our culture takes place entirely in transit. Even outside of the texts of the Torah, Jews have built our heritage from the perspective of the international, perpetual wanderer. Yiddish is every bit as Jewish as Hebrew and it is a hodgepodge of different languages from across Europe. Modern synagogues owe as much of their structure to the designs of our Christian neighbors in America as to our constantly evolving drive to reform. In Jewish culture, to be an outsider is to be at home. Perhaps that is why David, a king among kings, experiences one of the most important moments of his life in a foreign country.