The Song of Songs (part nine)

The eighth and final chapter of The Song of Songs is also the most opaque. Its language is removed and full of stacked metaphors, a nigh-exhausted conclusion to the emotional rollercoaster of Rayati's fight for love and personal liberty. It is at once sad and hopeful, finding our heroine having learned the complexity of the world and fully coming of age as a result.

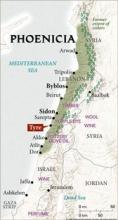

The chapter opens with the resignation that Dodi and Rayati will never be able to make a life together. In so many words, the lines express that social convention simply won't allow it, though it's not entirely clear what about their relationship is taboo, exactly. It may be that they are of two different nationalities, as much as distinct nationalities existed at the time, or possibly that they come from different social classes. This passage is an indication that their romance, while not ending, will never be official.

The next segment is cause for some debate. Depending on how it's translated, Rayati meets with Dodi under a tree either after Dodi has an argument with his mother, or possibly they meet under the same tree where Dodi himself was conceived. If it's the latter, then it's buried in the idiom of the time. Regardless, Rayati and Dodi are together in this passage and it's implied that they make vows to one another, even if a real marriage isn't in the future for them. Rayati says to Dodi, "Set me as a seal upon your heart, a seal upon your arm". This is a very clear reference to one of the oldest prayers in Judaism, the V'ahavtah, in which God tells His people to bind the mitzvot upon their own hearts and hands. Rayati and Dodi's relationship is posited here as nothing less than a holy covenant that trumps all other laws.

The reason they are making this covenant is because Rayati is about to become the property of King Solomon himself. In this segment the more traditional interpretation of The Song reads it as the official marriage of Solomon and Rayati, as if Solomon has always been Rayati's lover. This doesn't really follow, given the metaphors present here and the assaults on Solomon's character throughout the poem. Rayati mentions the vineyards of Ba'al-Hamon, how they were sold by Solomon for a 1,000 pieces of silver each. Now, Ba'al-Hamon is not a historical place. It's never mentioned anywhere but in this poem and its literal meaning (Master of the Multitudes) indicates another attack on Solomon. The vineyard in The Song is a symbol of personal fulfillment and natural joy. This line accuses Solomon of selling his own happiness as a ruler for material wealth, while the following line finds Rayati evoking her own vineyard, her own fulfillment. She implies that her vineyard will never truly be sold, saying, "The thousand is yours, Solomon".

And so The Song of Songs ends in quiet defiance. Rayati finds herself in the gardens (perhaps Solomon's gardens) and her friends ask her to sing a song. The song she sings is a measure from The Song of Songs itself: "Quickly, my beloved. Be like a gazelle or a young hart on the mound of spices". Though she is not with him, Rayati still holds out hope to be with Dodi again. Her song is this poem and with its help she is resolved to never completely relinquish her happiness for anything.